This Article is part of a series about the dials. Find the first dials article here.

Characters are a pain in the ass aren’t they? People build them up and get really attached to them. It’s like they are in some kind of relationship with their other-self.

If you kill one off in a modern game, you risk the chance of harming the psyche of a player, and it has to be this big campaign moment.

Want my advice? Just kill all of them off at third level and reveal that was the plan all along, make them make new characters, that’ll teach them…

Ahem. Maybe I am getting carried away. The point is that it is easy for a game to become about one set of characters played by one set of players and their deep emotional monologues and/or their daring action adventures.

Which is one style of play, sure.

It’s so popular it has become the default style of play. But it isn’t all, and the games that break that model often offer not only a different style of play but a different experience of interfacing with a roleplaying game.

So we are going to be spending this last dial looking at some alternative takes on the idea of character. But first, let’s see what we are doing by changing this relationship between character and player.

That First Paragraph Rant Becomes Relevant

In any work of performance, there is a connection between the work and the audience. This audience is fluid, and in roleplaying, the line between audience (in the form of player) and the protagonist (in the form of character) is paper thin.

This leads to a synergy of the two roles, with some players creating characters that are modelled on pieces of their personality or they develop deep motivations for. The default assumption for an RPG is that a player talks about their character as themselves, they say ‘I do this’.

D&D, in particular, has a design that facilitates this relationship – it’s social mechanics are often one roll, rather than complex back-and-forths, they fear more would disrupt a narrative moment.

This relationship echoes naturalistic theatre movements, some of which we discussed in the ‘No Am, All Dram‘ article, way back in last July. But in theatre, there are other movements and ideas about how we present the core argument or arc of a piece of art.

One of the most important scholars on this thought in the mid-twentieth century was Bertolt Brecht.

Brecht was a highly political German Marxist during the early twentieth century. On his return from World War I, he observed the rise of fascism in his country and wrote plays that opposed the nascent Nazi party. Eventually, he fled Germany when Hitler came to power.

He believed that theatre’s job was to educate the masses and that theatre as it stood at the time was woefully incapable, with people’s emotional engagement with a protagonist causing them to ignore the bigger picture the play might be trying to convey. While he had tunnel vision brought about by experiences that informed this viewpoint, his writings were a bombshell on the performance community.

So why are we discussing a German Marxist playwright from the forties? Well, I think Brecht’s viewpoint is also relevant to RPG play.

A lot of players lose themselves in their character, and while that’s admirable for immersion, it sometimes leads to a ‘that’s what my character would do’ or heartbreak when a character suffers some kind of setback.

It can also lead to players who spend several sessions seeming engaged, playing to the hilt – but having no idea what the overarching plot is.

None of these things are game killers. But we can disrupt these behaviours by engaging in what Brecht called ‘Verfrumdungeffeckt’. That is a moment inside a work that reminds you that this is not real.

In plays, Brecht used alienation techniques to make people remember they were watching a play and that the play had a point, disrupting the relationship between the audience and the work. They then took a moment to gauge where the narrative was going and why, guiding their attention back to what the performance had intended.

Now of course, in a play, you can be can be railroady as you like with this, even disregarding that the idea of authorial intent as guiding force had been eroded by the late 20th century. But in a game we aren’t doing that, we’re telling a story together. We can utilise that distancing effect to create bigger stories where we zoom the scope in and out to take players out of the immediate concerns of their characters.

Just imagine for second running a DnD game where instead of playing one adventurer, each player controls four characters during a war. They can send different characters on different missions and engagements. Some of them might get captured, stuck behind enemy lines or gain promotions and such.

While character development for each character might be less, the larger story you tell as a group will be wider in scope and create a unique experience. And when one of those characters dies ignobly, the player has three others and feels like the world has consequences without feeling burned.

This is Verfrumdungseffeckt in practice. We’ve messed with the relationship between player and character by adding more and only visiting some of them some of the time.

This is just one potential example of a way a game might shake up and introduce this disconnect. As opposed to D&D, the game Masks puts heavy mechanical influence on the effect social interactions have on a character.

It means that players are always aware that those social situations have a mechanical impact. The effect on the audience is that they are Always Thinking about how their character feels, beyond simple embodiment, into analysis. This means they are focusing on how words and actions can affect relationships, which is arguably what the game is about.

Now we are all on the same page about the whys and wherefores, next session we will go practical and discuss modes we can play in our games and how they affect play.

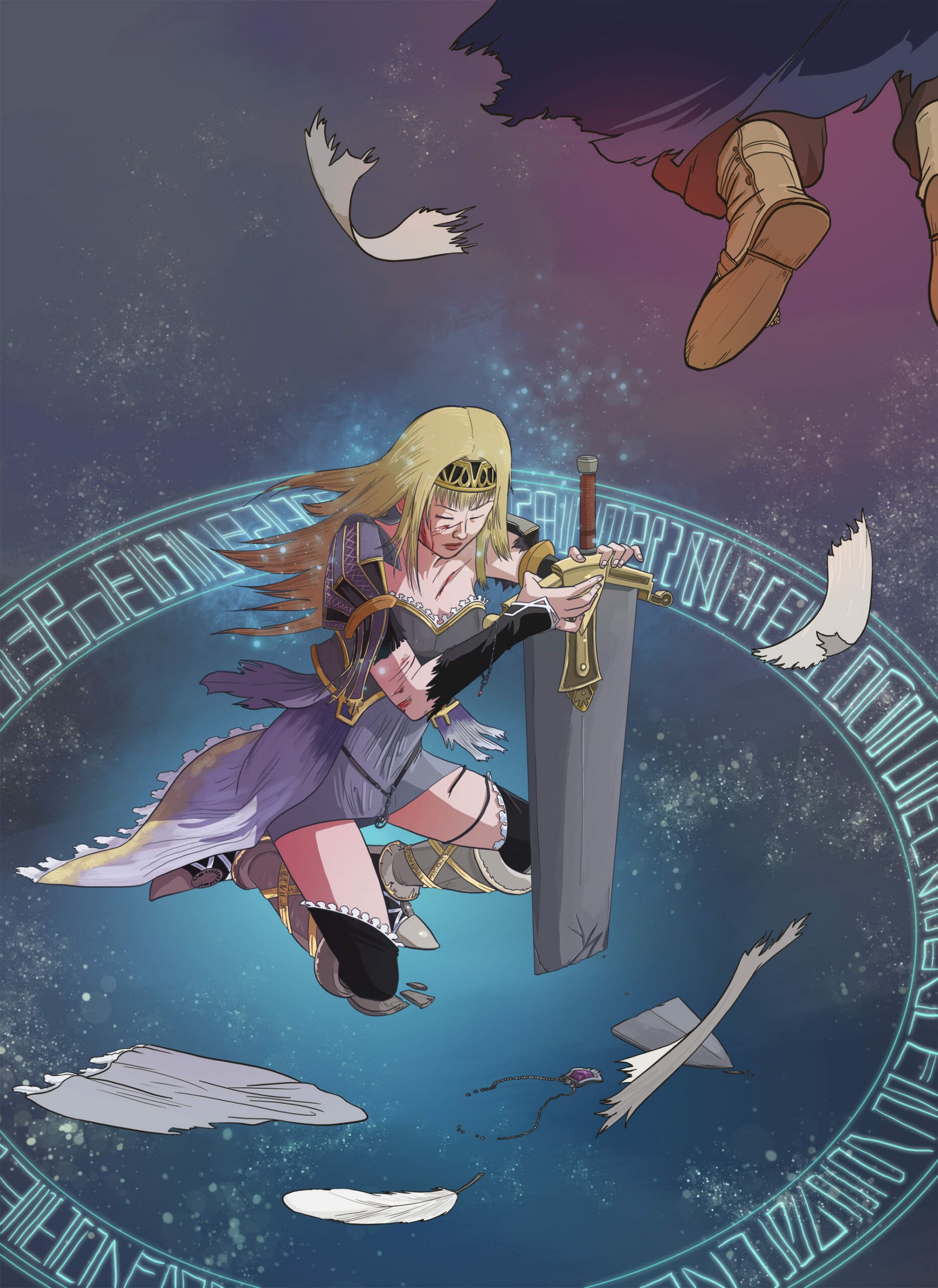

Creative Commons credits: He Is Mine by Joazzz2, Defeated Valkyrie by Pehesse, and Shackles of Death by free4fireYouTube.

You can find thoughts and opinions on this article in the comment section below.