Duncan Rhodes has a background that makes him uniquely qualified to write a book on setting the scene.

As a professional travel writer and blogger based in Barcelona, he knows exactly what makes a location feel alive, lived-in, and worth exploring. He has taken that “wanderlust DNA” and applied it to tabletop gaming in his new book, The Creative Game Master’s Guide to Extraordinary Locations.

With a foreword by the legendary Ed Greenwood, the book aims to stop Game Masters from settling for generic stop-offs and start creating session-sustaining set pieces.

I caught up with Duncan to discuss how real-world geography inspires fantasy maps, the secret to versatile encounter design, and why you should never forget the smell of a location.

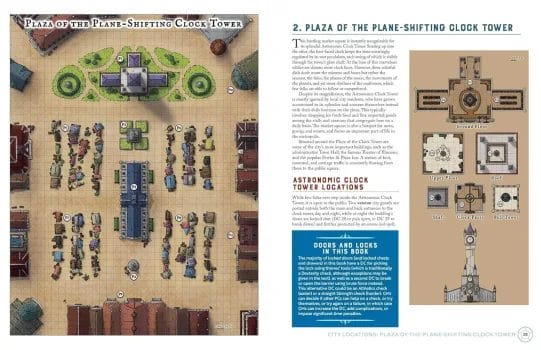

You have a secret weapon that most RPG designers don’t: a background as a professional travel writer and blogger living in Barcelona. How much of that ‘wanderlust’ DNA ended up in this book? For instance, when you were designing the Plaza of the Plane-Shifting Clock Tower, were you channelling real-world spots like Prague or Krakow? I’d love to know which location in the book is the most autobiographical!

Absolutely, my travels have a huge influence on my world-building and the Plaza of the Plane-Shifting Clock Tower is a great example. The layout of the square is almost identical to Krakow’s Rynek, with the Sukiennice (Cloth Hall) in the middle reimagined as the Amber Arcade, while the Plaza’s Town Hall is borrowed from Wroclaw’s Town Hall, and the Clock Tower is inspired by the colourful dials of Prague’s Astronomical Clock. These European squares and monuments are splendid to behold in real life, and full of activity, and it’s easy to fill a fantasy version of them with potential drama (fairs, fights, rumours, public addresses, festivals and omens could all feature!). I also borrowed one of Krakow’s legends when writing up the Plaza… that of heroes being transformed into pigeons, ready to return to heroic form when the city needs them most.

Outside the city, the Flooded Quarry Hideout is inspired by my swims in Zakrzowek quarry (when it was still abandoned), while the coastline around the Church of the Salt Oracle mimics the dramatic shores of the Costa Brava (just north of Barcelona). On the same map, the “ridge-riding staircase” that leads to the Church is borrowed from Gaztelugatxe in the Basque Country (it was also used as the staircase for Dragonstone in Game of Thrones).

Whenever I’m travelling, I am always thinking… wouldn’t it be cool if some orcs / cultists / wyverns sprang out here and there was an epic fight? (I never leave home without my longsword…).

In your introduction, you draw a line in the sand between functional ‘stop-offs’ (like a generic smithy where you just buy a sword) and true ‘Adventure Locations.’ For a GM feeling stuck in a rut of generic fantasy tropes, what is the single biggest game-changer for turning a boring map into a session-sustaining set piece?

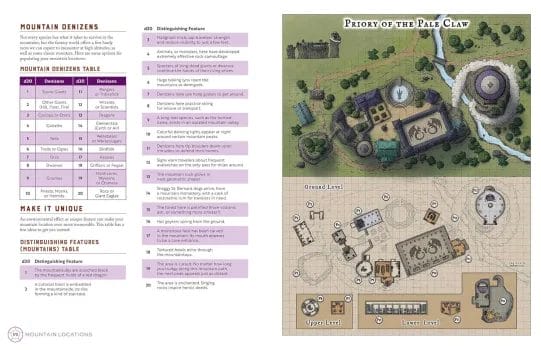

To support an entire session of adventure (or more!), a map needs to contain opportunities for at least two, preferably all three, of D&D’s core pillars… namely: combat, exploration and social interaction. In the case of a hostile location, like a dungeon or lair, you probably want to focus more on opportunities for the first two pillars and then deploy the classic tools available to all fantasy Game Masters: monsters and traps. And of course you need some hidden treasure to incentivise this combat and exploration.

For a “civilised” location, including interesting NPCs and/or factions, with conflicting motivations to the players, is the easiest way to ensure dramatic social interactions… which may well lead to combat. While players often ignore opportunities to explore in safe / civilised locations, I always try to include a few interactive features on my maps, that curious players can poke at to perhaps gain a benefit or learn a secret.

Another thing to consider if you are designing, or shopping for, a good map is scale. A map of a two-room temple can only support so much fun… so what about developing an entire temple zone, with maybe some natural terrain features and hazards, and perhaps other ruins and remnants from the same or other cultures? You also want the map to be big enough to stage a dynamic combat, with features that incentivise combatants to move around the “board”.

You’ve mentioned that Mammoth Hall was designed with ‘versatility’ as a guiding principle—players could heist it, fight the giants, or even, as you put it, ‘free the mammoths for animal rights!’ How difficult is it to design a map that accommodates a ‘guns blazing’ party and a ‘stealth and social’ party without breaking the narrative?

Not only the Mammoth Hall, but all the locations in the book are designed to be as versatile as possible. I didn’t want to write level-dependent adventures, with a linear storyline dictating how these 30 locations should be used. Because when you do that you make it much harder for GMs to use the material you created. I wanted to provide rich settings, ripe with adventure potential, that GMs can deploy as they please, either using some of the adventure hooks I suggest along the way, or coming up with their own.

Designing a location that can be solved with violence or with stealth is more or less the same process for me. You place the treasure in a safe place, and add locks, traps and guards, according to what’s credible. And if the players think they can defeat the guards with violence (and then take their sweet time with the locks etc) they are welcome to try!

Generally speaking though, most of the locales in The Creative Game Master’s Guide to Extraordinary Locations are inhabited by an entire community, making violence a low percentage ploy for most parties. If, however, the GM expects the players to use violence and/or they want to encourage a good old fashioned hack’n’slash, they can use GM fiat to dictate that half of the community is away on business (i.e. reduce the combat threat at the location so it’s manageable for the PCs).

Another good technique for running a violent raid is to give the PCs allies and just challenge the players to do their part in a larger operation. Perhaps the players team up with an orc tribe to raid Mammoth Hall, and the orc chieftain says: “my warriors will take out the frost giants in the longhouses, you outsiders must deal with the Jarl in his hall”.

I’m a huge fan of the ‘Twelve Extraordinary Location Design Tips’ chapter, specifically the idea of rolling on random tables for ‘Building Materials’ or ‘Epithets.’ What is the weirdest or most surprising location combination you rolled up yourself while playtesting these tables? Did a ‘Chocolate Fortress of Despair’ ever almost make the cut?

Ha! Well yes, I rolled up a fair few zany results. If you like high, whimsical fantasy the epithets design technique is a really great tool! I actually had to cut down my table of epithets quite a bit to fit it in the book… maybe I’ll publish the full table on my blog one of these days! The technique works well because you are often forced to imagine how something incongruous, or nonsensical works. One example result I mention in the book is The Chained Baths. When I rolled that, I started to imagine a cleanliness-obsessed despot who forces all travellers to their city to be chained up and scrubbed before they are allowed to enter the city gates. It wasn’t quite interesting enough to be considered an adventure location, but I might use the idea as the player’s first introduction to a foreign city sometime in the future, when I want to mess with them!

The Flying Ballroom Palace features a zero-gravity dance floor and a ‘Fey Stone’ that can turn guests into centaurs or force them to speak in rhymes. It feels like a playground for roleplay-heavy groups. Do you have a favourite ‘disaster scenario’ that unfolded during playtesting when players started messing with those magical buttons?

The Fey Stone is one of my favourite creations in the book, and is a specific tool designed to solve a specific problem which GMs face… making social events interesting. I was speaking on a podcast the other day to a fellow DM (pretty sure it was with Isaac from Setting the Stage!) and we both admitted that the way we always make a grand ball dramatic is to have a fight break out… or else someone gets assassinated mid-gala. We’ve both overused that technique to the extent that our players now expect an NPC to drop dead at any moment!

However, when I deployed the Palace of the Flying Ballroom in my Waterdeep campaign recently, I was actually able to run a set-piece social event without having to resort to violence. Players were having trysts in hedge mazes, bantering with NPCs over games of croquet, and holding secret conversations on the palace’s boating lake, all the while trying to speak backwards, or mimicking a tiger and growling “raaawrrrgh!” at the end of every sentence, thanks to the magic of the Fey Stone. I am sure GMs can have some fun extending the Fey Stone’s table of effects too!

We have to address the case of mistaken identity: You often get confused with the other Duncan Rhodes, the miniature painting legend. Since you actually include painting tips in your blog occasionally, have you ever considered leaning into the chaos and creating a magic item or NPC in your books that references ‘Two Thin Coats’ just to mess with us?

No, but I am now! Other Duncan has definitely given me some pause for regret, as I was a very keen painter in the early 90s and half decent too (or so I thought)… maybe I should have stuck with it! After a 30 year hiatus, I’m pretty rusty however. Now I just use painting to “come down” after a writing session, otherwise my brain keeps firing into the early hours and I won’t sleep until dawn. (Although, for a supposedly relaxing pastime, painting Warhammer is very fiddly and annoying!).

You managed to snag a foreword from the Archmage himself, Ed Greenwood! That’s quite a seal of approval. What was it like collaborating with the creator of the Forgotten Realms, and did he give you any specific advice on making these locations feel ‘lived in’ and history-rich?

Ed is such a kind guy and has been a real ally to me. We started trading the occasional email when I wrote Candlekeep Murders: The Deadwinter Prophecy and sent him a copy. I couldn’t believe it when he read the adventure immediately and gave me some wonderful feedback. Since then we’ve remained lightly in touch and, of course, with his unparalleled world-building legacy, he was my first choice to introduce this book of settings.

The Fallen Idol Tavern is such a vivid spin on the starting hub built inside a defunct religious school with a giant toppled statue pointing imperiously at the bar. It implies so much history just by existing. When you’re world-building, do you usually start with the visual hook (the giant statue) or the social hook (the failed school turned tavern)?

Good question. I am not 100% sure if I follow a pattern here! I do remember with the Fallen Idol that I really wanted to create a beautiful, sprawling coach-house-style pub, as a great base that GMs can use for their campaigns. But I was very conscious of the fact that maps of such taverns already exist already, so I spent a long time thinking: “what can distinguish my pub?” At some point I came up with the idea of a colossal statue breaking through the roof as a defining feature, and then more ideas started flowing from there. Plus, of course, I had to answer the question… what was the statue’s original purpose? I knew too that I wanted a ghost that fined people for swearing, so finally I was able to join the dots and bring the whole location together satisfactorily.

Referring back to your earlier question about using material from my travels, I also drew inspiration from Budapest’s “ruin pubs” to expand the Fallen Idol tavern into an entire complex. Budapest’s kerts are – for my money – the best bars in the entire world. They typically occupy a whole floor or two of an abandoned apartment block with different functions allocated to each room (bar, restaurant, nightclub, ping pong table, bike hire, cinema etc… all in one complex). A long time ago, I actually wrote a fun article about these crazy Budapest bars on one of my blogs, in case you’re interested!

One thing that stands out in the Firefly Bazaar is the sensory detail; the smell of spices and chocolate, the flickering light of the firefly lamps. Do you think GMs often overlook the ‘travel guide’ aspect of describing a scene? What’s one sensory trick you use to make a location feel real to players who are just staring at a battle map?

Yes, I think you’re right that GMs often overlook these sensory details… and too often so do I! I’m actually glad you found an example where I did a better job than usual! My advice to myself, as well as anyone reading, is to run a mental checklist of all five senses during the location creation process and be sure to include some non-visual stimuli in your descriptions. Aside from increasing immersion, maybe considering what the air smells like in this ravine, or what the lichen tastes like in this cavern, will lead to some intriguing new feature or detail for your location…

The book includes ‘Adventure Paths’ like Menhirs, Manticores, and Murder! that string these locations together. For GMs who want to take this book and run a full campaign, do you see these 30 locations as a standalone world, or are they meant to be dropped into the Forgotten Realms or a homebrew setting like loose puzzle pieces?

100% the latter. They are designed to be modular locations you can copy and paste into other settings, namely the world you’re using right now! The Adventure Paths are there to show how – with a little thought – you can easily create links between your favourite locations to create longer adventures or even mini-campaigns. But I don’t really expect people to play those Adventure Paths as written… they are more to demonstrate what’s possible, and that it’s actually pretty easy to link these locations together, within your own world, if you so wish!

A huge thanks to Duncan for taking the time to share his insights. It is fascinating to see how the discipline of travel writing—noticing the small details, the history, and the sensory experience of a place—translates so perfectly into the art of the Dungeon Master.

Duncan Rhodes is the blogger behind Hipsters & Dragons, and also the author of The Creative Game Master’s Guide to Extraordinary Locations (& How To Design Them), which is available on Amazon, Barnes & Nobles, Indigo, and hobby stores around the US and Canada.